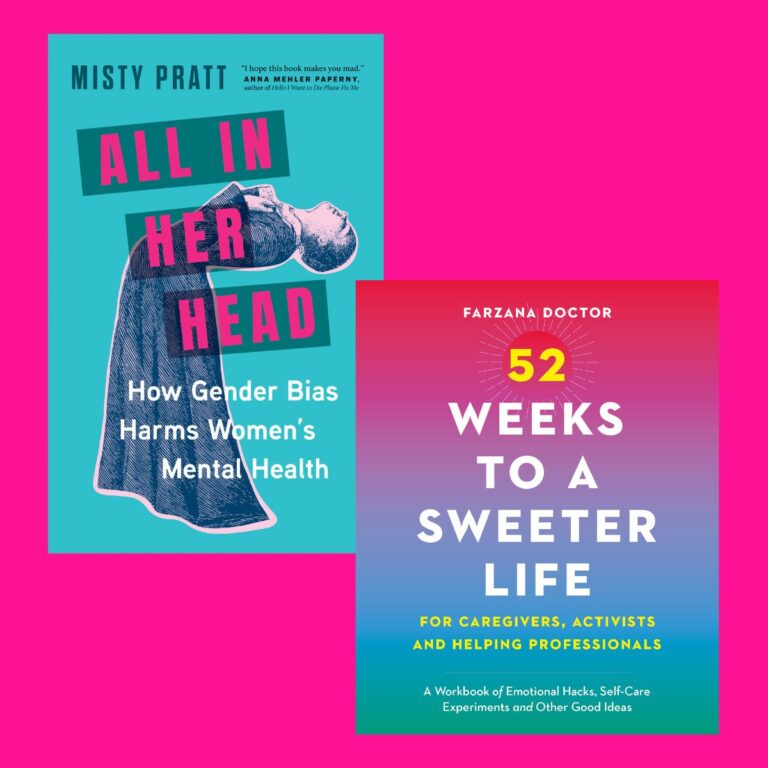

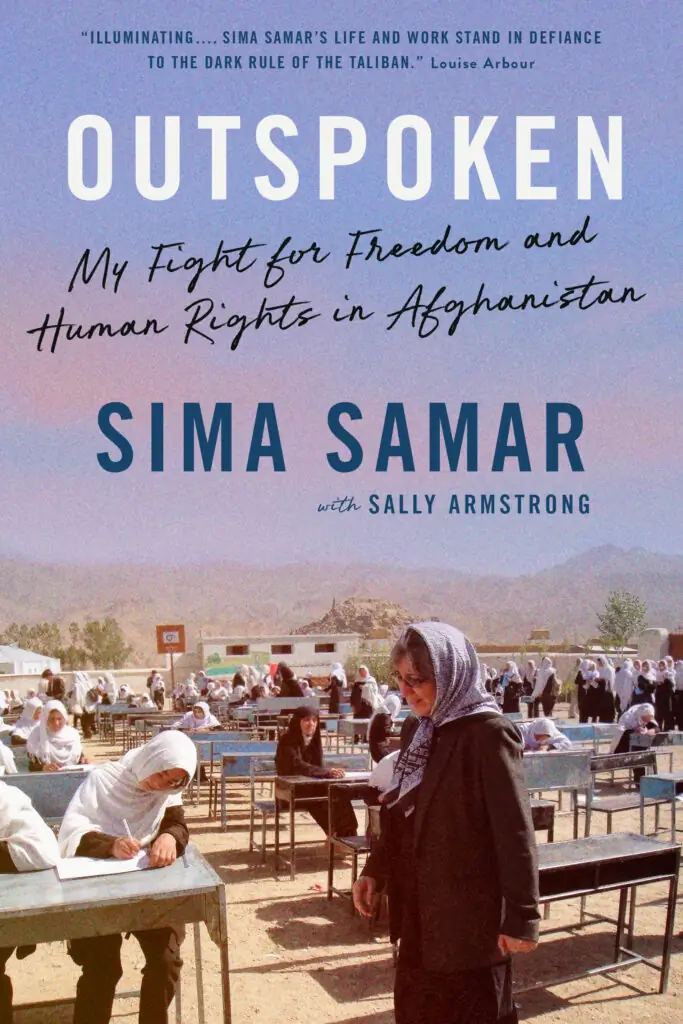

Outspoken: One Woman’s Fight for Freedom and Human Rights in Afghanistan

Books24.02.2024

Dr. Sima Samar has been fighting for equality and justice for most of her life. Born into a polygamous family in Afghanistan, she learned early that girls had inferior status, and she had to agree to an arranged marriage if she wanted to go to university.

By the time she was in medical school, she had a son, Ali, and had become a revolutionary. After her husband was disappeared by the pro-Russian regime, she escaped. With her son and medical degree, she took off into the rural areas — by horseback, by donkey, even on foot — to treat people who had never had medical help before.

Sima Simar has gone on to serve as Afghanistan’s Minister of Women’s Affairs, has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize and continues to be a thorn in the side of the Taliban, and The Honest Talk is pleased to bring you this exclusive excerpt from her soon-to-be released memoir Outspoken, written with award-winning Canadian journalist and human rights activist Sally Armstrong and published by Penguin Random House Canada.

The presentation of the Call for Justice report with UN Special Representative Jean Arnault, me, Un High Commissioner for Human Rights Louise Arbour and President Karzai; 2004

What exactly is “the war on terror”? What do we actually mean when we speak of “endless war” and “perpetual war”? Humanitarian law and war are a contradiction in terms, and yet we pursue both.

And what happens to people during this period? We know conflict destroys buildings and bridges and that it kills mothers and fathers and children. But it also damages the way we act as citizens. Our behavior is shaped by the fear and anger and unpredictability that war brings. How can we imagine that forty-five years of war, and in particular the last eighteen years of suicide bombings and improvised explosive devices and attacks on our public institutions, will not contribute to emotional instability in Afghanistan?

The people are caught between the extreme left (communism) and the extreme right (Islamic fundamentalism). They’re in the mid- dle, with justice and peace up for grabs. I’m fascinated by how much we study war, analyze war, make movies about war and write about war, and yet never find the formula to stop it. That suggests to me that we’ve been looking for peace in the wrong places. Most wars today are civil wars. They are about insurgents and terrorists, usually rogue leaders and people who follow them blindly.

Historians say war has become easier to start and harder to stop. They also say Afghanistan will likely be the last international intervention that includes foreign boots on the ground. This is a possibility that all of us, not just Afghans, need to examine, because there are consequences for everyone. War is so destructive to human relationships; it makes even ordinary people resort to violence. In Afghanistan, and in every other war-torn country, poverty increases, and it is children, people with disabilities and women who get the worst of it.

I remember seeing a child on the street during the first Taliban takeover; he was screaming his head off and all alone. The smoke from a bomb in his village was still rising. It was just one of many stark examples of how the suffering of children is part of the tapestry of conflict.

In war’s aftermath the people are yoked to its consequences. Most suffer from the psychological trauma that comes with insecurity; others — the homeless ones, the orphans, the wounded, the malnourished —suffer no less grievously. All of them are pay- ing the price for someone else’s feud, and without help they grow up and keep the war kettle boiling, carrying the quarrel to the next generation.

Writing a prescription for the mother of a newborn baby (© 2001 Courtesy of Olivia Heussler, Zürich)

And where does it end? It ends in places like the Hills of the Martyrs, a field with mudbrick houses scattered about that has become the resting place of the girls from Sayed Al-Shuhada school, the moms and babies from the Dasht-e-Barchi Hospital, and so many more from different attacks. I often ask myself why grandiose cast-iron statues of men on horseback with guns raised triumphantly are the monuments of war in the city centers of the world, while the blameless victims are buried together in ceme- teries far away. Traditionally, when people died in the city their families took them back to the region they’d come from to bury them with their ancestors. But the increase in terrorist attacks in the west end of Kabul has moved people to claim the two rock- strewn dusty hills behind the school as a cemetery.

The cemetery came to be in July 2016, after an attack on people who were peacefully marching to demand a newly built electricity line to supply their neighborhood. Suddenly, the government had soldiers and barriers on the road that blocked the marchers’ way to the city. Hundreds of men, women and even children were stopped nd trapped in the middle of the road — a perfect target for the suicide bomber looking to strike. More than three hundred were injured, and eighty-six people died, most of them young boys and girls. It was decided to honor them as martyrs and to bury them on the hills not far from where they died. The government tried to stop this, but the voice of the people rang out louder than the grumbling of the politicians.

Suicide attacks had been rare in Afghanistan until 2006 but have since increased every year, influenced by jihadis outside of our country who began targeting mosques, sports clubs, wedding cele- brations and election centers—wherever people gathered in large numbers. And the victims were mostly children dreaming to build a civilized, democratic Afghanistan. They found peace on those two little hills on the west side of Kabul.

While there had been other attacks, and children had been killed before, the May 2021 assault on girls leaving their school was like a rumbling coming from the core of the earth. It told all of us that inhumane terrorist killings were picking up speed. Even religion wasn’t slowing the attackers down—the Taliban spokes- man had warned: “Jihad during Ramadan is more valuable in the eyes of God the Almighty!” Although the Taliban claimed not to be responsible for the attack, the terrorist factions are intercon- nected: the Taliban, iskp, and other bloodthirsty groups — all know what the other is up to.

The truly perplexing thing about all of them is that women and education are their Achilles’ heel. Consider this: Between 1996 and 2001, women, who represent 50 percent of the population, were treated like slaves and like baby-making machines (and the more male babies, the better). Women could not speak out or talk back — they had no rights and lived obediently and submissively at home, suffering no end of violence. In 2001, when the Taliban was defeated, a lot of that changed; for the next twenty years, girls could go to school and become lawyers, journalists, governors, ministers, members of parliament, senators, teachers, doctors, entrepreneurs, artists and sportswomen. The universities were crammed with girls and boys who were reaching for the stars and imagining lives of fulfillment and success.

Scrubbing for surgery at the Shuhada Clinic in Quetta, 1997

The young women had been joining the workforce as executives, and the government as ministers, and the judiciary as judges. In August 2021, they were even on the negotiating team that went to Doha, Qatar, for discussions with the Taliban to find a way to end the years of conflict. What’s more, today 64 percent of Afghans are under the age of twenty-five. The Taliban may try to take their rights away, but they cannot erase the knowledge of the majority of its young citizens.

As summer began in 2021, many here were very afraid. So was I. We had stopped trusting the foundation on which the progress of the last two decades had been built. I kept reminding myself to look at what we’d accomplished: the institutions we built, the human rights record that’s in progress, women taking their rightful place beside men in government and business, a flourishing media. After all that, after building and facilitating a democracy, imagine losing it all again. That is a loss not only for Afghans but for all people and countries who believe in human rights and democratic values.

I know the inside story of my country––the hijacking of the religion, the dishonesty, the collusion, the corruption, the self-serving leaders. I know the courageous women and men who have lifted the country to heights we had only imagined. And I know the blameless ones who simply want peace and a chance for their children’s future. I have been an eyewitness to the us effort, to nato’s work, to the un, the international community, and our own military. I know the players in this chess game called Afghanistan.

As a woman and physician, as a politician and activist, as a human being who has spent a lifetime witnessing one paroxysm of violence after another, I can say this: The hopes and dreams of the girls at Sayed Al-Shuhada school were the same as mine. Those girls perished simply because they were girls, because they dared to go to school to learn to think for themselves. They are my story. And I was their age—twelve—when I became aware that my country needed change.