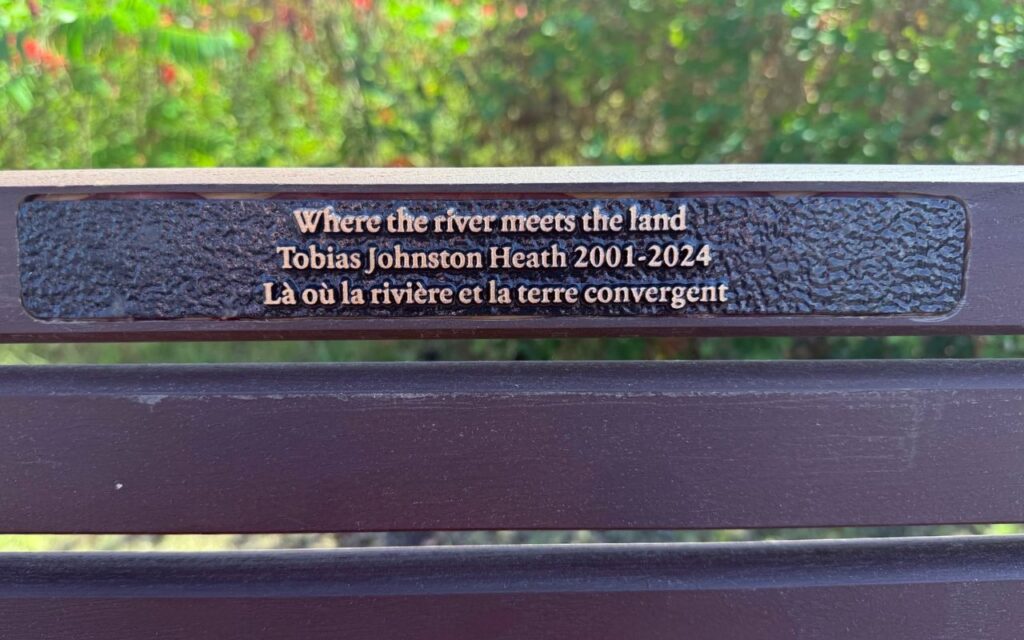

For Pari Johnston, there is one place in the city where she goes to feel extra close to her son Toby: a bench along the Ottawa River Parkway.

It’s a special spot, surrounded by greenery and the calm waves rippling through the waterway.

“Toby walked there all the time, particularly when he was struggling,” she said. “He would get out and walk and feel best along the river.”

When the family lost Toby in 2024, their friends and family erected the bench in his memory – a place for others to sit, reflect, and enjoy a moment of pause.

“Toby was a really complicated, complex, and wonderful person,” Johnston said. “He was incredibly funny – the funniest person in our family. He loved physical humour, British humour, and he had this great, infectious laugh.”

He was also athletic and had a deep love for nature.

“He played competitive soccer all through his teens,” she said. “And his best friend was our cat – she was his greatest comfort.”

Living through loss

As a teenager, however, Toby began to struggle. School, social life, and home life became increasingly difficult, and the family turned to the mental health system for help. But what they didn’t yet know was that Toby wasn’t living with a mental illness – he was autistic. That diagnosis didn’t come until he was almost 18.

“We went through five or six years of really challenging times,” Johnston explained. “He was misunderstood. Toby was incredibly bright, and he was masking a lot of his struggle. Most of the support systems weren’t autism-informed. There are still huge gaps in understanding when someone has a dual diagnosis.”

By the time he was hospitalized, Toby’s anxiety and depression had deepened. And, following several misdiagnoses, including the family being told he was struggling with schizophrenia, Toby became very mistrusting of the medical system as a whole.

Johnston believes those experiences – and a world that often felt harsh and unforgiving to her son – left Toby feeling hopeless.

“He was very troubled by where the world was going. He always cared for the underdog,” she said. “And I think he just started to feel that life in this world was too harsh for him. He lost hope.”

When Toby died by suicide at 23, Johnston made a deliberate choice to be open about his passing.

“It was never a question of hiding anything,” she said. “I love him so much, and I think it was really important to not shy away at all about telling our story… to show that families like ours exist, and that you can try to live well despite catastrophic loss.”

That openness has shaped how she navigates grief, how she leads in her role as President and CEO of Colleges and Institutes Canada, and as an advocate for mental health, autism and housing issues in the city.

“When I returned to work, I shared pictures of Toby and talked all about him,” she said. “I needed my team to know there would be days I wasn’t okay, and that was okay. It was much better than pretending to be superhuman.”

Keeping memories alive

What Johnston wants people to know most is that it’s okay to talk about Toby – and to talk about grief.

“People worry that they will say the wrong thing, or that mentioning him will upset me,” she said. “But he’s always on my mind. It’s much harder when no one says anything at all, or pretends like nothing happened. In my view, there’s never a wrong thing to say. It can be as simple as, ‘How are you? I know you must be thinking of Toby.’”

For Johnston, sharing Toby’s story is also about meaning. She hopes that by speaking openly about his life and the struggles he faced, other families and young people navigating similar challenges feel seen, understood, and less alone.

“Ultimately, I need our pain, and his pain, to mean something…I need to make sense of it,” she said. “I suppose it’s helped with my own healing as well to be open and vulnerable, and I hope that helps someone else.”

Finding happy moments

A year later, Johnston admits she is still learning how to live alongside her grief.

“There’s no right way, there’s no playbook,” she said. “There are days when I’m knocked to my knees, and other days when things are fine. I try to give myself grace for all of it.”

But most importantly, she and her family continue to bring Toby into their everyday lives through rituals, memories, and small gestures that keep him close.

“He was very precise about everything,” she said with a laugh. “When we have cake, we still cut it exactly the way he would have, in perfectly equal slices, and we laugh about it. We still talk about him all the time. He’s part of our family.”

Her grief has also deepened her empathy.

“I give people a lot of grace now,” she said. “I don’t sweat the small stuff. I ask for help when I need it, and I lean on my friends. I recognize more and more how critical it is that I continue to live well without Toby. He needed to make the choice he did, and I understand it, and I love him so much. But I have to keep living for myself, my younger son and my family. I think that’s really important.”