I’m more than just my diagnosis: Living with 22q

Health10.06.2024

When I was just 20 months old, my parents were told that I might never graduate college or be able to live on my own.

This was because doctors had just diagnosed me with “DiGeorge Syndrome” — most commonly referred to these days as 22q Deletion Syndrome.

What it meant was that a part of my 22nd chromosome was completely nonexistent. Although I’m almost positive that this is your first time hearing about this syndrome, it is the second-most-common deletion syndrome behind Down Syndrome.

Symptoms range across the board, but for me personally, 22q showed up in the formation of two holes in my heart — VSD and ASD — not meeting typical developmental milestones (like walking, for example), and not being able to make sounds properly.

Any diagnosis is life-altering, and in the year 2000, when there wasn’t much information about the syndrome available, my parents had to pave their own path in the dark — and so did I.

My mom became a superwoman and took me to countless doctor’s appointments, developmental therapy sessions, tests, and more, while my dad was a superman and went to the office every day as they both faced the uncertainties of what living with a child with 22q meant.

The reality was that living with 22q made my childhood atypical. I spent many hours at Lurie Children’s Hospital and various doctor’s offices. I became a pro at MRIs, blood tests, and ultrasounds by the age of six. In elementary school, I was continually taken out of classes for speech and occupational therapy.

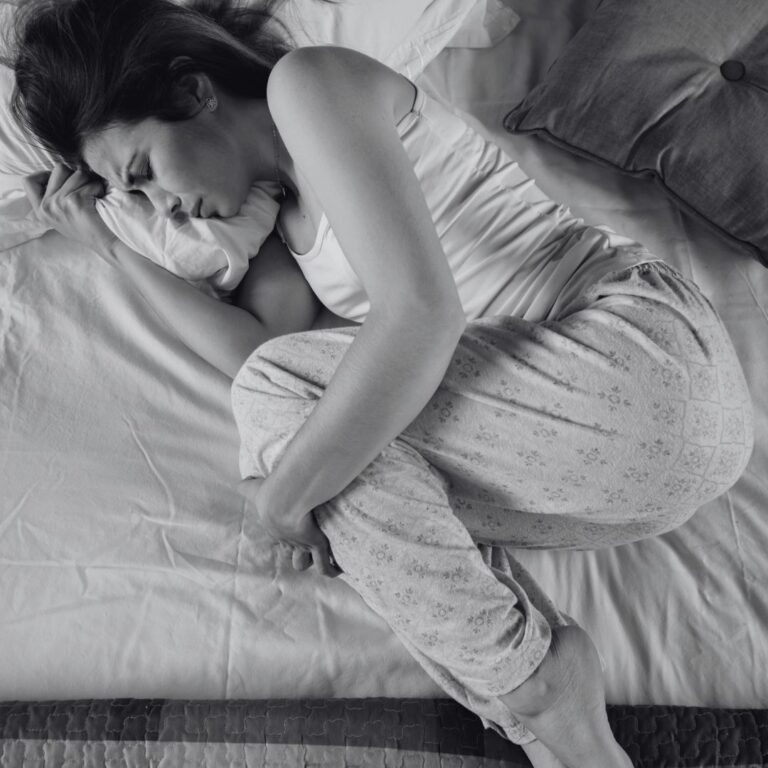

For most, it’s easy to look back at your childhood and think, “Ah, those were the good days.” And, while I look back at most of my childhood and come to the same conclusion, it’s not really a one-and-done answer.

Reflecting back on my childhood-to-adolescence journey often comes with a spectrum of complicated feelings, but it can be summed up in one word: juxtaposition.

I had a happy childhood, yet half of it was occupied by appointments and sessions. I had friends, but I often felt left behind due to my low immunity and developmental delays in school.

I saw the value in being “different” or “unique” while also longing to be “normal.”

Not surprisingly, these feelings heightened even more during middle school. It’s safe to say that even kids without 22q feel these things during that time. You’re figuring out who you want to be and who to associate yourself with, all while your body is changing and growing. Of course, you’re bound to feel like an outsider!

Through this, a mantra of sorts entered my life: “You are not your diagnosis.”

My parents always made sure I knew that yes, 22q is a part of me, but it’s not all of me, and despite what doctors may have told them in that hospital room all the way back in 2000, my diagnosis does not limit me.

This influenced me to persevere and pave my own path.

I joined a band in high school and played on the same stages as Slash and Green Day.

I graduated college with a degree in Creative Writing.

After I graduated, I moved halfway across the country to be a cast member at Walt Disney World without knowing anyone there. I have my own studio apartment and my own full-time job.

When people pass me on the street, they don’t see the 22q girl.

They see a woman in her 20s living her life in the city, experiencing and feeling the same things that other women in their 20s do.

Because I’m more than just my diagnosis.