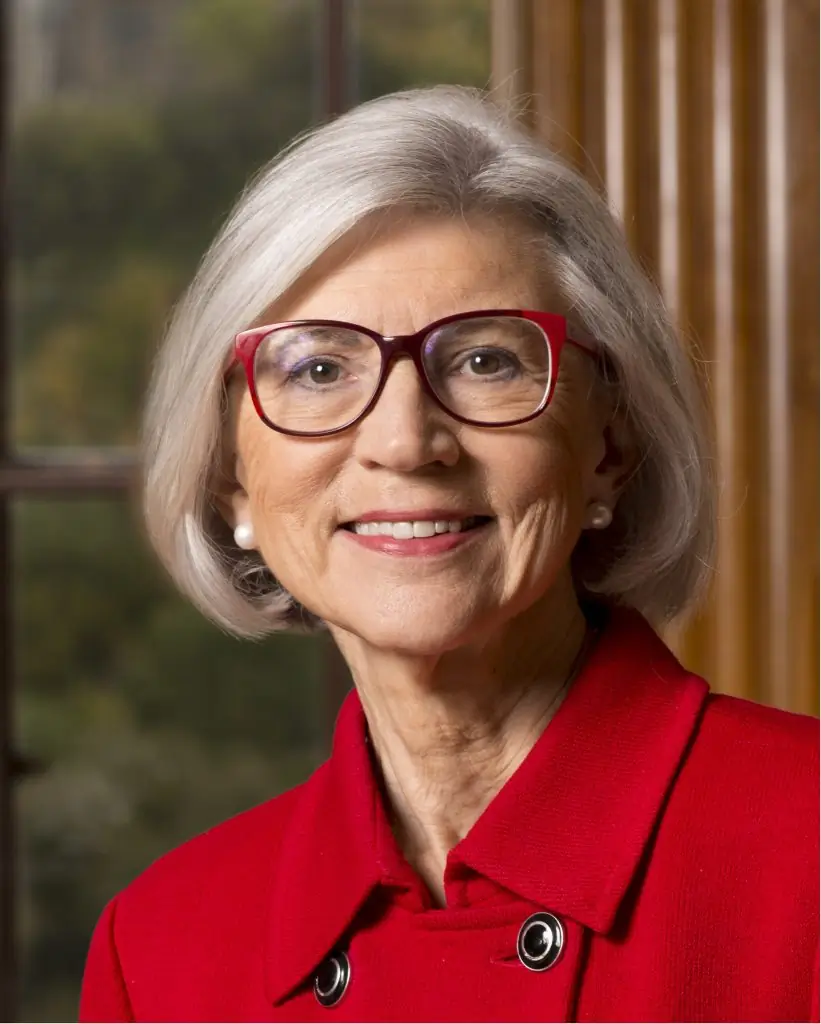

Beverley McLachlin – The first female and longest-serving Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada

The Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin was the first female and longest-serving Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada. Raised in a log house without electricity, plumbing, or running water in the foothills of Alberta, she grew up to become one of the most respected jurists in Canadian history. Now retired from the Court and the author of two bestselling books, Chief Justice McLachlin speaks candidly about the highs and lows of her extraordinary life.

Note: This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Her childhood in Pincher Creek

Jennifer Stewart: Tell me about growing up in Pincher Creek. What are some of your strongest memories?

Beverley McLachlin: It was an existence that I thought was very normal but isn’t to urban people. I lived on a ranch; it was gorgeous scenery. On the side, there were good discussions and conversations and learning; there was diversity because Indigenous people came to work for us and lived nearby. However, in those days, things were very separate. I went to school for the most part, apart from one year when I did homeschooling.

Catherine Clark: You were a voracious reader, and the Pincher Creek library was an important place for you growing up. Is it true that you read essentially every book in that town’s library?

Beverley McLachlin: I’m sure I didn’t read every one, but all the ones that interested me. This was a wonderful thing for me because there wasn’t ready access to books. We had no bookstore or anything like that, and with this public library that these ladies of the town organized and ran, they got quite a few books together. When I was seven or eight or nine, I worked my way through the juvenile section, and then after I pretty much exhausted that I moved on to the adult section.It allowed me, in my very restricted rural setting, to experience other civilizations and history — it was a glimpse into other worlds

Jennifer Stewart: Your mother always wanted a university education, and life got in the way. How did her inability to go to university impact your pursuits?

Beverley McLachlin: I always felt that it was a very special thing and an important thing, and I wanted to have opportunities beyond what my mother had been able to do. More than that, I wanted to explore and find out about the world. My mother was always a voracious reader, too; she always had novels on the go. So she influenced me — stories were an important part of our life.

Getting into law school as a woman

Catherine Clark: Was it your decision to study law, something you planned?

Beverley McLachlin: I was fortunate to have enough scholarship money to do whatever I wanted. I decided to go into the arts and just learn about the world. I ended up getting into philosophy. I liked philosophy; it helped me to think straight. I liked the analytic approach that it taught me. I was going to do graduate work in philosophy, but I was becoming less and less enamoured of it. Then, when I was in my final year of undergraduate honours philosophy, my then-friend whom I later married said to me, “You should consider law; I think you’d be a good lawyer.” I’d never thought about that; I didn’t know any women who’d been successful at law — this was in the mid-60s. So, I was at the ranch during the summer and wrote a letter to the dean, addressed to the Dean of the Faculty of Law, University of Alberta. And I said, “Could you send me some information?” And four days later, I got a letter saying I was accepted. So I was astonished. But I thought, “Why don’t I try it?” I’ve been in the law ever since.

Jennifer Stewart: Did you face discrimination in law school?

Beverley McLachlin: I can’t give you the exact number, but about 10 per cent of the class were women. And this was before the ‘70s when women went in fairly large numbers to law school. We were still a novelty, and the atmosphere was very masculine. I have to say my male colleagues were fine, but there were incidents — you might not be invited to certain things that they all went to because they were masculine events; some professors would single out some women in a way that was not entirely appropriate and professional; and then sometimes even the content of how things were taught, like sexual assault which at that time we called it rape, almost with a light-handed kind of touch. It was pretty upsetting, and I and a couple of other women went to talk to the dean about that. Nothing happened. I led the class in the first year, and normally that meant I would have been asked to be editor of the Law Review, but I was not, and they chose a man over me. So there were annoyances and disappointments, but my attitude was I couldn’t change the world.

Unlike philosophy, law school was a man’s world, and even though they acted in ways they thought were appropriate, we understand that it was inappropriate in today’s light.

Catherine Clark: Did you feel isolated in any way? For instance, you said you went to the dean, and your concerns weren’t addressed.

Beverley McLachlin: It takes a long time to change the world. And if you are going into a world that’s dominated, and has been for time immemorial, by masculine attitudes and values and just the insensitivities — a lot of the time nobody means anything wrong, but they don’t understand that it is belittling or excluding. I tried to speak up when I could, but I had to accept the world I was in; the only other option would be to get angry, and then I would have become dysfunctional in that world, so I wasn’t going to let that happen.

Being a judge through turbulent times

Catherine Clark: After law school, you had quite a remarkable series of professional experiences. And you were appointed to the bench. And then you were appointed Chief Justice of the Superior Court of BC. At that time, your first husband passed away, and it was just a few months before you were appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada. You also had a young son. What was going through your head?

Beverley McLachlin: Giving up my professional career was never an option. It had become who I was and what I wanted to do. I would have been lost if I had to give it up. When I was asked to go to the Supreme Court of Canada, I said to my son, I think we’ve had too much happening in our lives, with losing your father, with me taking this new job as Chief Justice, and now this would mean moving and going to a different part of the country. And I said I don’t think this is our time to do it. The following day, he said, “Mom, I think you should do it.” He was only 12. And my first husband had always said I would be on the Supreme Court of Canada. So all these crucial indicators in my life were saying, “Go for it.” So I did.

Catherine Clark: One of the Chief Justice decisions you presided over in the Supreme Court was assisted dying legislation. How do you think that conversation about dying needs to evolve in Canada?

Beverley McLachlin: It is a deeply divisive issue because many people, and I respect these views, believe that allowing someone to end their life before it is taken away from them is morally wrong. And I don’t suggest that people shouldn’t be respected in that view. But I have always believed you cannot force that view on everyone. Our Charter of Rights guarantees us fundamental liberties, and one of those liberties, I think, is a choice not to take your life to the bitter end — and painful is the operative word. I say, have these conversations and let people make their choices.

Catherine Clark: Given the current climate and situation, how do we ensure more diversity on the Court so that regular Canadians see themselves reflected at the highest levels? How do we get there?

Beverley McLachlin: We’re getting there, but it’s a slow process in the court system. There’s a slow time trajectory in that you must put in a lot of time before becoming a judge. That’s not bad, but I think younger people have a place on the bench — I became a judge at 37. But what this means for diversity is that you have to combine that long trajectory with another fact: until relatively recently, we weren’t attracting many minority people to the study of law. Until recent decades, very few Indigenous people went to our law schools. It’s been a slow process because of those two factors. I’d like to see a lot more diversity. We have some, but we need a lot more.

Current life

Catherine Clark: Does this seem like a pivotal time to you? Does it appear different than the past decades? How do you feel about this 2020 era we’re living in?

Beverley McLachlin: Well, it’s a time of change and unravelling. On the trust thing, though, polls consistently show that around 80 percent of Canadians trust their institutions. That’s high; the comparable figure in the States is just above 20 percent, which may be why we’re doing better on the COVID fight than our friends to the south. People trust when their health leaders and premiers and prime ministers say, “This is what we need to do.” But getting back to your point, this is a time of significant change. The way we saw the world, the way we thought our institutions should operate, the way we saw our society — we now see it differently. These fundamental things we’re grappling with, like racial rifts, were always there, but we are now very aware of them.

Catherine Clark: Chief Justice, what’s next for you?

Beverley McLachlin: I’m swamped. I must say I miss the Court. I miss judging. But the time had come when I had to move on. And I’m certainly not ready to give up the law even yet. So, I’m an external judge on the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal. I sit on the Singapore International Commercial Court. I’m doing arbitration — commercial arbitration, mainly, and mediation. That’s continuing my learning curve in the law into a new area. And I’ve been doing a lot of writing — I’ve written a novel, which I’d always wanted to do, and I was shocked when it was published. And I wrote my memoir. I’m busier than I can ever remember being, but it’s fun.